When talking about malaria, a mosquito‑borne disease caused by parasites that infect red blood cells. Also known as parasitic fever, it poses a serious health risk in many tropical regions and can turn a vacation into a medical emergency if you’re not prepared.

Understanding Plasmodium, the genus of microscopic parasites that cause malaria is the first step in grasping why the illness spreads the way it does. Five species—P. falciparum, P. vivax, P. ovale, P. malariae and P. knowlesi—each have their own fever patterns, severity levels, and preferred habitats within the human body. P. falciparum is the deadliest, often leading to cerebral complications if treatment is delayed. The parasites live inside red blood cells, hijacking them to replicate, which explains the hallmark fever‑chills cycle that many travelers recognize only after the fact. Meanwhile, the mosquito vector, primarily the female Anopheles species that bites at night acts as the delivery system, picking up parasites from an infected person and passing them to the next host. This biological chain means that controlling mosquito populations directly cuts malaria transmission, a fact public‑health officials have known for decades.

When it comes to stopping the disease before it starts, antimalarial medication, drugs like atovaquone‑proguanil, doxycycline, and artemisinin‑based combos are the cornerstone of both prophylaxis and cure. The choice of drug depends on the destination’s resistance profile, the traveler’s health status, and how long the stay will be. For example, in areas where P. falciparum is resistant to chloroquine, artemisinin‑based combination therapies (ACTs) are the frontline treatment. Prophylactic regimens usually begin a day or two before entering a risk zone and continue for a week after leaving, ensuring that any parasites that might have entered the bloodstream are eradicated before they can cause symptoms. Side effects vary—some people experience mild stomach upset, others get photosensitivity—so a pre‑travel consultation with a healthcare professional is essential.

Beyond drugs, malaria prevention leans heavily on personal protection measures. Using insecticide‑treated bed nets, applying EPA‑approved repellents containing DEET or picaridin, and staying in screened or air‑conditioned rooms dramatically lower bite risk. Environmental strategies—such as draining standing water, applying larvicides, and introducing fish that eat mosquito larvae—help communities reduce the breeding grounds that sustain Anopheles populations. For travelers, combining these tactics with medication creates a layered defense that most experts agree is the most effective.

Finally, travel health isn’t just about packing medicine; it’s about staying informed. Pre‑trip vaccination records, up‑to‑date country risk maps, and a clear plan for seeking medical care if fever develops are all part of a comprehensive strategy. Knowing the local health infrastructure, carrying a rapid diagnostic test kit when venturing into remote areas, and having a travel insurance policy that covers emergency hospitalization can make a life‑saving difference.

Below you’ll find a curated collection of articles that dive deeper into each of these topics—detailed symptom checklists, step‑by‑step guides for choosing the right prophylaxis, mosquito‑control tips for households and communities, and real‑world travel stories that illustrate how to stay safe in malaria‑endemic regions. Use this resource to arm yourself with the knowledge you need before you board your next flight.

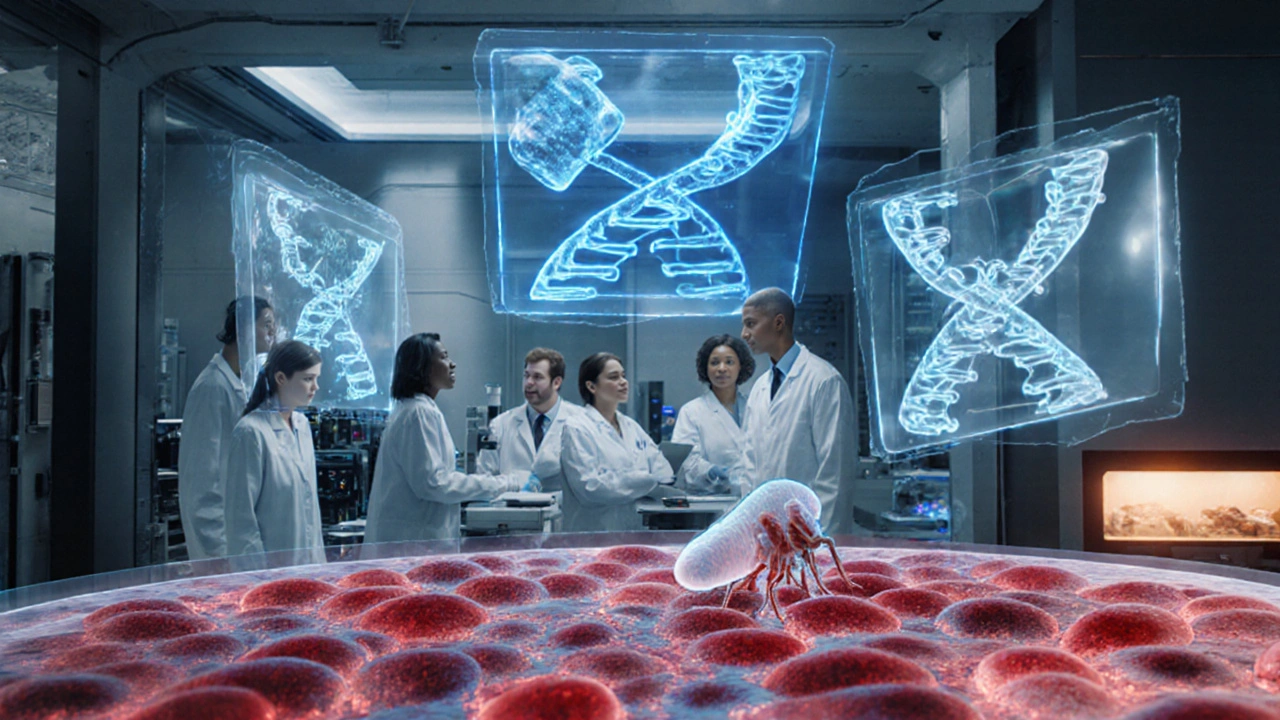

Explore how decoding the human genome and parasite DNA, plus CRISPR and new vaccines, are reshaping malaria research and moving us toward a cure.

READ