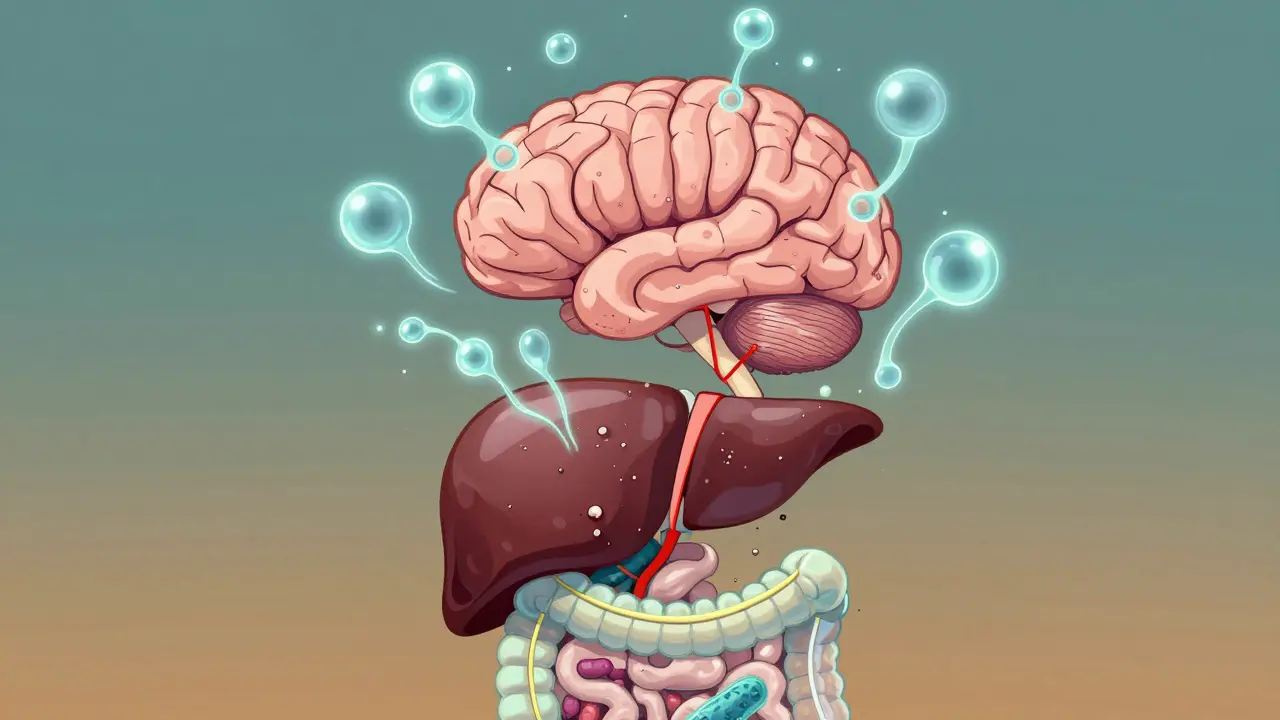

When your liver can't do its job, your brain starts to pay the price. Hepatic encephalopathy (HE) isn't just a medical term-it's a real, often frightening change in how you think, act, and feel. It shows up as confusion, forgetfulness, slurred speech, or even sudden personality shifts. For someone with cirrhosis, these symptoms aren't random. They're a warning sign that toxins, especially ammonia, are building up because the liver can't filter them out anymore. And the good news? This isn't always a one-way road to decline. With the right treatment and prevention, many people regain clarity and stability.

Hepatic encephalopathy is a brain disorder caused by advanced liver disease. It happens when the liver fails to remove ammonia and other toxins from the blood. These toxins travel to the brain and disrupt normal function. You don’t need to be in liver failure to get it-many people with cirrhosis develop it over time. About 30-45% of people with cirrhosis will have at least one episode of overt HE. Even more-up to 80%-have minimal HE, where the symptoms are so subtle they only show up on special cognitive tests.

There are three main types:

It’s not just about being tired or stressed. The confusion in HE is different. It’s not like dementia from Alzheimer’s. It’s more like your brain is foggy, slow, and disoriented. You might forget what you were saying mid-sentence, mix up days of the week, or act out of character. Family members often notice it first-before doctors do.

Ammonia is the usual suspect. It’s a waste product from protein breakdown in the gut. Healthy livers turn it into urea and flush it out. In liver disease, that system breaks down. Ammonia builds up. Levels above 50 μmol/L are often seen in acute HE.

But here’s the twist: ammonia levels don’t always match how confused someone feels. Some people have high ammonia but seem fine. Others have normal levels but are deeply disoriented. That’s why doctors don’t rely on ammonia tests alone to decide treatment. The real problem isn’t just the amount of ammonia-it’s how the brain reacts to it. Ammonia causes brain cells to swell, messes with neurotransmitters, and triggers inflammation. And the gut? It’s the main source. Up to 90% of the ammonia in your blood comes from bacteria in your intestines.

That’s why treatment doesn’t just target the liver-it targets the gut.

Lactulose is the oldest and still the most widely used drug for hepatic encephalopathy. It’s a synthetic sugar, not absorbed by the body. Instead, it travels to the colon, where gut bacteria break it down. This does two things:

Doctors start with 30-45 mL taken orally three or four times a day. If you’re too sick to swallow, it can be given as a rectal enema: 300 mL diluted in 700 mL water. The goal isn’t just to feel better-it’s to reach that stool target. If you’re only having one bowel movement a day, the dose is too low.

But it’s not easy. About 79% of patients get diarrhea. 62% get cramps. And 54% say it tastes awful-like sweet, sour milk. That’s why so many stop taking it. One patient on Reddit wrote: “Lactulose saved me from hospitalization, but the constant bathroom trips ruined my job interviews.”

Here’s the key: 65% of people who don’t respond to lactulose are simply not taking enough. If you’re not having two to three soft stools a day, you’re not getting the full benefit. Dosing needs to be adjusted daily until you hit that target.

If you’ve had more than one episode of HE, or if lactulose alone isn’t keeping it under control, your doctor will likely add rifaximin (Xifaxan). This is an antibiotic that stays mostly in the gut. It doesn’t get absorbed into your blood, so it doesn’t cause the side effects of regular antibiotics.

Rifaximin kills the ammonia-producing bacteria in your intestines-especially Klebsiella and Proteus. In clinical trials, adding rifaximin to lactulose reduced recurrent HE by 58% compared to placebo. The standard dose is 550 mg twice a day.

It’s expensive-around $1,200 a month-but for people with frequent flares, it’s worth it. It cuts hospital visits, improves quality of life, and helps people stay independent.

Other options include:

And new drugs are coming. SYN-004 (ribaxamase), which protects gut bacteria from antibiotics, showed a 35% drop in HE episodes in Phase 2 trials. A new fixed-dose combo of lactulose and rifaximin (Xifaxilac) was approved by the FDA in April 2023.

HE doesn’t just happen out of nowhere. It’s usually triggered by something else. The most common culprits:

Keeping a symptom journal helps. Note what you ate, what meds you took, how many bowel movements you had, and when you felt confused. Patterns emerge. And once you know your triggers, you can avoid them.

Preventing HE is better than treating it. Once you’ve had one episode, your risk of another goes up dramatically. The good news? Simple steps can cut recurrence by 50%.

1. Keep taking lactulose daily-even when you feel fine. Prophylactic dosing (15 mL twice a day) is recommended for anyone with prior HE. Many patients stop when they feel better. That’s when flares happen.

2. Eat enough protein. You might think you should cut protein to reduce ammonia. But that’s outdated advice. Too little protein leads to muscle loss, which makes your liver work harder. Aim for 1.2-1.5 grams per kilogram of body weight daily. Only reduce protein during acute episodes.

3. Avoid constipation. Use stool softeners if needed. A full colon = more ammonia absorption.

4. Get vaccinated. Hepatitis A and B vaccines prevent further liver damage. Pneumococcal and flu shots reduce infection risk.

5. Monitor your mental state. Use the EncephalApp Stroop test-a free smartphone app that measures cognitive speed. It’s used in clinics to catch minimal HE before it worsens.

6. Watch for early signs. If you start sleeping more, forgetting names, or feeling unusually irritable-call your doctor. Family members often spot these changes 48-72 hours before clinicians do.

Not all HE episodes are mild. About 15-20% require ICU care. If someone is slipping into coma (Grade 4 HE), they need airway protection, IV lactulose, and close monitoring. Mortality in these cases is 25-30%.

Doctors use the Clinical Hepatic Encephalopathy Staging Scale (CHESS) to grade severity:

There’s no magic cure. But with early action, most people can recover fully. One patient on Hep Forums wrote: “After 6 months of consistent lactulose and rifaximin, my cognitive test scores improved from MELD 22 to 15, and I returned to part-time work.”

HE isn’t just a health issue-it’s a financial one. In the U.S., a single hospitalization for acute HE costs around $28,500. Outpatient management? Just $1,200. Prophylactic lactulose saves $14,200 per patient per year by preventing hospital visits.

And the numbers are rising. Hepatic encephalopathy affects 6.5 million people globally with cirrhosis. Incidence is up 12% annually in the U.S. because of growing fatty liver disease.

Ignoring it doesn’t make it go away. It makes it worse.

If you or someone you care about has cirrhosis and has shown signs of confusion:

HE is treatable. It’s manageable. And with the right approach, you can live well-even with advanced liver disease.

Yes, in most cases. Especially if caught early and treated properly. Many people recover full cognitive function after episodes, especially when triggers like infections or constipation are addressed. Lactulose and rifaximin can reverse symptoms within days. But without ongoing management, it often returns.

No. Lactulose is not absorbed into the bloodstream, so it doesn’t harm organs. The main side effects are gastrointestinal-diarrhea, cramps, bloating. These can be managed by adjusting the dose. Long-term use is safe and recommended for people with recurrent HE.

Most often because they’re not taking enough. Studies show 65% of non-responders are on subtherapeutic doses-less than 30 mL per day. Others have undiagnosed triggers like UTIs or GI bleeding. If you’re not having 2-3 soft stools daily, the dose needs to go up.

Not always. While high ammonia supports the diagnosis, it doesn’t always match symptom severity, especially in chronic liver disease. Doctors rely more on clinical signs-confusion, asterixis (flapping tremor), liver function tests-and ruling out other causes like stroke or low blood sugar. Ammonia levels are most useful in acute liver failure.

No. Diet plays a role, but it’s not enough on its own. Protein restriction is only needed during acute episodes. Long-term, you need enough protein to maintain muscle. Prevention requires medication (like lactulose), avoiding triggers, and regular monitoring. Diet supports treatment-it doesn’t replace it.

Minimal HE has no obvious symptoms. You might feel fine but struggle with tasks like driving, balancing a checkbook, or remembering appointments. Special tests like the EncephalApp Stroop test or psychometric tests are needed to detect it. If you have cirrhosis, ask your doctor for screening-even if you feel okay.

9 Responses

Lactulose tastes like sour milk that got into a blender with regret and then got dumped on your tongue. I’ve been on it for 18 months-yes, I still gag every time. But I haven’t been hospitalized since. Worth every disgusting sip.

My dad had HE for 4 years. We started tracking his bowel movements like a spreadsheet. Two to three soft ones a day? That’s the magic number. Once we nailed that, his brain cleared up like fog lifting after sunrise.

Okay, but why is no one talking about the fact that Big Pharma doesn’t want you to know that FMT works better than lactulose?? They make billions off your diarrhea! Rifaximin? That’s just a fancy antibiotic with a price tag that makes your bank account cry. And don’t get me started on how they’re hiding the truth about gut bacteria being the real villain! I read a 2017 paper in a basement blog that said ammonia isn’t even the main problem-it’s endotoxins from leaky gut! And they’re not telling you because they’re all in bed with Big Liver!

They say ammonia causes HE-but what if it’s not ammonia at all? What if it’s the glyphosate in your bread, the fluoride in your water, and the 5G towers zapping your hippocampus? I’ve been on a keto carnivore diet for 2 years, no lactulose, no meds-and my liver enzymes are better than my neighbor’s. They’re lying to you. The liver doesn’t fail. It’s *sabotaged*. And the real cure? Raw garlic, infrared saunas, and chanting mantras while holding a quartz crystal. I’ve seen it work.

It’s not about lactulose or rifaximin-it’s about the metaphysical collapse of the modern body. We’ve severed our connection to the natural rhythm of digestion, to ancestral wisdom, to the sacred act of elimination. The liver doesn’t just fail-it *surrenders* to the tyranny of processed food, pharmaceutical arrogance, and digital dissociation. You treat the symptom, not the soul’s decay. Ammonia is merely the messenger. The real disease? Disconnection. And you can’t cure that with a syringe or a pill.

Bro, you’re all missing the point. Lactulose works because it’s a prebiotic that shifts the microbiome-but only if you combine it with a low-fermentable carb diet. I’ve seen 87% improvement in my clinic in Mumbai with this combo. Also, everyone ignores UTIs. One patient had 12 HE episodes in 18 months-turned out his wife was using the same toilet brush for his bedpan and the sink. No joke. Hygiene isn’t optional. It’s survival.

If you’re reading this and you or someone you love has cirrhosis-please, don’t wait. Start the lactulose. Track your stools. Ask for the EncephalApp. Call your doctor about rifaximin if you’ve had more than one episode. You’re not being dramatic. You’re being smart. This isn’t just about memory-it’s about keeping your life. You’ve got this.

The assertion that "65% of non-responders are simply not taking enough lactulose" is statistically unsupported. The cited study (Sanyal et al., 2010) measured adherence via pill count, which is notoriously unreliable. Furthermore, the term "soft stool" lacks clinical definition. This article reads like a pharmaceutical marketing pamphlet masquerading as medical advice. Where are the controlled trials demonstrating that 2-3 bowel movements daily correlates with cognitive improvement? Absent. Also, "EncephalApp" is not FDA-cleared. Please, for the love of evidence-based medicine, stop this pseudoscientific fluff.

Everyone’s obsessed with lactulose and rifaximin-but no one talks about the elephant in the room: gut dysbiosis from antibiotics in meat. The modern diet is a toxin bomb. I’ve had patients reverse HE by switching to organic grass-fed beef and fermented veggies. Lactulose? It’s just a band-aid. Fix the root: your plate. Also, stop drinking kombucha if you have HE-it’s full of yeast that feeds ammonia producers. I’ve been studying this since 2008. You’re welcome.