Almost every sexually active person will get HPV at some point in their life. It’s not a rare or shameful infection-it’s normal. The human papillomavirus (HPV) is a group of over 200 viruses, and about 40 of them affect the genital area. Most go away on their own without causing symptoms. But a few high-risk types, especially HPV 16 and 18, stick around and can lead to cancer. These two types alone cause nearly 70% of all cervical cancers worldwide. And they’re also linked to cancers of the anus, throat, penis, vulva, and vagina.

Here’s the thing: cervical cancer doesn’t happen overnight. It takes 10 to 20 years for an HPV infection to turn into cancer. That’s a long window to catch it early-and stop it before it becomes dangerous. That’s why vaccination and regular screening aren’t just good ideas. They’re life-saving.

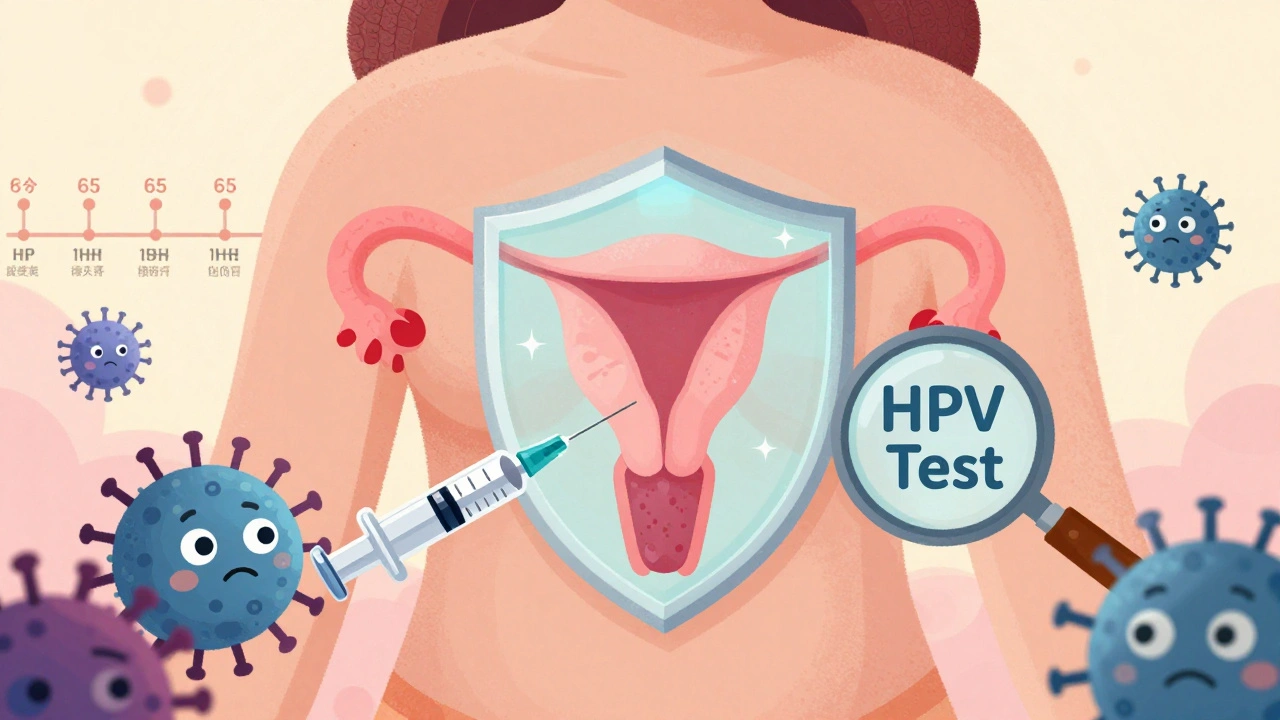

The first HPV vaccine, Gardasil, got FDA approval in 2006. Since then, we’ve seen better versions come out. The current vaccines protect against nine types of HPV, including the two most dangerous ones (16 and 18) and several others that cause genital warts and other cancers.

It’s most effective when given before any sexual activity begins. That’s why health agencies recommend vaccination for kids aged 11 to 12. But it’s not too late for older teens and adults. The CDC says the vaccine is still beneficial up to age 26. And in 2020, the FDA expanded approval for people up to age 45. If you’re between 27 and 45 and haven’t been vaccinated, talk to your doctor. You might still benefit, especially if you haven’t been exposed to many HPV types.

The vaccine doesn’t treat existing infections. But it prevents new ones. Studies show it reduces precancerous cervical changes by more than 90% in vaccinated groups. Countries like Australia and Sweden, where vaccination rates are above 80%, are on track to eliminate cervical cancer entirely by 2030. That’s not science fiction-it’s happening right now.

For decades, the Pap test was the only way to screen for cervical cancer. It looked for abnormal cells on the cervix. But it wasn’t perfect. It missed a lot of early changes, especially in women over 30.

Today, the gold standard is HPV testing. Instead of looking for cell changes, it checks for the virus itself. That’s smarter. If you don’t have high-risk HPV, your risk of cervical cancer in the next five years is extremely low. A 2023 study in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute found that women with a negative HPV test had only a 0.23% chance of developing serious precancer in five years. Compare that to a negative Pap test, where the risk was 0.51%-more than double.

Two FDA-approved HPV tests are used in the U.S.: the cobas HPV Test and the Aptima HPV Assay. Both detect 14 high-risk types. The cobas test even separates HPV 16 and 18 from the others, which helps doctors decide how urgently to follow up.

Screening guidelines changed in 2020 and 2021, and they’re now simpler and safer.

The American Cancer Society and U.S. Preventive Services Task Force both agree: HPV testing every 5 years is the best choice for most people. It catches more problems earlier and requires fewer visits over time.

One of the biggest barriers to screening is discomfort-or fear-of pelvic exams. Many women skip screening because of this. That’s why self-collected HPV tests are such a big deal.

In 2024, Kaiser Permanente officially added self-collection to its guidelines. Women can now swab their own vagina at home using a simple kit. Studies show it’s just as accurate as a test done by a clinician. Sensitivity is 84.4%, specificity is 90.7%. That’s nearly the same.

Real-world results are even better. In Australia and the Netherlands, offering self-collection boosted screening rates by 30-40% among women who hadn’t been screened in years. In the U.S., the CDC says 30% of cervical cancers happen in women who’ve never been screened. Self-collection could change that.

Some states now allow pharmacies to distribute self-collection kits. Others are piloting mail-in programs. This isn’t the future-it’s here.

A lot of people think: “I got the vaccine, so I don’t need Pap tests anymore.” That’s a dangerous myth.

The vaccine protects against the most common cancer-causing types-but not all of them. There are over 14 high-risk HPV types. The vaccine covers nine. That means 5-10% of cervical cancers still come from types not in the vaccine.

The CDC is clear: vaccinated women follow the same screening schedule as unvaccinated women. Skipping screening because you’re vaccinated puts you at risk. You’re protected, but not invincible.

Despite all the progress, cervical cancer isn’t the same for everyone. Black women in the U.S. die from cervical cancer at a rate 70% higher than White women. Why? It’s not biology. It’s access.

Women in rural areas, low-income communities, and marginalized groups often can’t get to clinics. They don’t have transportation. They don’t have time off work. They don’t trust the system. Or they’ve never been told they need screening.

Low- and middle-income countries face even bigger gaps. Only 19% of women in these regions have ever been screened. In high-income countries, it’s 80%. The WHO’s 90-70-90 goal by 2030-90% vaccinated, 70% screened, 90% treated-is ambitious. But without equity, it won’t work.

Research is moving fast. A 2023 study from Wayne State University showed that after two negative HPV tests, the risk of cancer drops so low that screening every six years might be safe. That’s a possibility for future guidelines.

Artificial intelligence is also stepping in. In January 2023, the FDA approved Paige.AI, an AI system that analyzes Pap smear images. It helps pathologists spot abnormalities faster and more accurately. In places with few trained doctors, this could be a lifeline.

And globally, the cost of HPV tests is dropping. New, cheaper tests are being developed for low-resource settings. Self-collection kits are being redesigned to work without refrigeration or lab equipment. These aren’t distant dreams. They’re in trials right now.

HPV isn’t going away. But cervical cancer can be. We have the tools. We know how to use them. What’s missing now is consistent action-and the courage to ask for help.

Yes. The HPV vaccine protects against the most common cancer-causing types, but not all of them. Screening is still needed to catch the remaining high-risk types. Follow the same screening schedule as unvaccinated people: HPV testing every 5 years starting at age 25, or Pap tests every 3 years if HPV testing isn’t available.

Yes. HPV is linked to cancers of the anus, throat (oropharyngeal cancer), and penis. Men can also pass HPV to partners, even without symptoms. Vaccination protects men from genital warts and reduces transmission. The vaccine is approved for males up to age 45.

Self-collected HPV tests are nearly as accurate as clinician-collected ones. Studies show they detect 84-90% of precancerous lesions. They’re not perfect, but they’re good enough to be a major breakthrough for women who avoid screening due to discomfort, fear, or lack of access. Kaiser Permanente and other major health systems now accept them as a valid option.

HPV testing is more sensitive-it finds the virus before cell changes happen. A negative HPV test means you’re very unlikely to develop serious cervical changes in the next five years. Pap tests look for cell changes, which can take longer to appear. That’s why Pap tests needed to be done more often. HPV testing gives longer protection with fewer false alarms over time.

A positive HPV test doesn’t mean you have cancer. Most infections clear on their own. If you test positive for HPV 16 or 18, you’ll likely be referred for a colposcopy right away. If you test positive for other high-risk types, you’ll usually get a Pap test (reflex cytology). If both are abnormal, you’ll be referred for further evaluation. Only a small fraction of positive HPV results lead to treatment.

Yes. Under the Affordable Care Act, HPV screening and vaccination are covered at no cost for most private insurance plans and Medicaid. Medicare also covers Pap tests and HPV tests for eligible individuals. Self-collection kits are increasingly covered too, especially through state public health programs.

HPV is everywhere. But cervical cancer doesn’t have to be. We have a vaccine that works. We have tests that catch problems early. We have ways to make screening easier and more accessible. The science is clear. The tools are here. What’s left is to use them.

Don’t wait for symptoms. Don’t assume you’re not at risk. Don’t skip screening because it’s uncomfortable or inconvenient. The next time you hear about HPV, remember: this isn’t just about sex. It’s about survival.

15 Responses

The government pushes this vaccine because they get kickbacks from Big Pharma. They don't care if you get cancer. They care about the profit margin.

Screening? Just a distraction. They want you dependent on the system.

This is the same moral cowardice that allows societies to ignore the natural consequences of sexual promiscuity. Vaccination is not a substitute for virtue. You cannot outsource morality to a needle.

Human beings were never meant to live in a sterile, sanitized world where every biological risk is engineered away. This is not progress-it is spiritual decay.

So let me get this straight. We're told to vaccinate 11-year-olds because sex is inevitable... but we're also told not to talk about sex?

Also, the word 'cervical' is spelled wrong in the title. I'm not even mad. Just disappointed.

You think this is about health? No. This is about control. Who gets to decide what bodies are safe? Who profits when women are afraid to look inside themselves?

Self-collection kits? Still controlled by the same institutions that silenced us for centuries.

This is so important!! 💪 Seriously, if you’re reading this and haven’t talked to your doctor about HPV screening yet, do it today. You’ve got this!! 🌸❤️

And if you’re a parent-just get that vaccine. It’s one of the best gifts you can give your kid’s future.

The notion that vaccination negates the need for personal responsibility is a dangerous fallacy

One cannot outsource ethics to a pharmaceutical company and expect societal cohesion

Yet here we are

They say HPV is common. So why is it suddenly a cancer crisis now? Coincidence? Or did the CDC just reclassify normal cell changes as precancer to justify more tests and more money?

My cousin got a positive HPV result and they wanted to cut her cervix out. She didn’t even have symptoms.

vaccines r a scam. they inject u with lizard dna and track u via your cervix. i read it on a blog. also pap smears are just the gyno’s way of feelin u up. i got a self kit. i swabbed my own vagina and mailed it. they sent me a bill for $4000. they know.

I appreciate the clarity and depth of this post. In India, access to screening remains a challenge, especially in rural areas. But initiatives like mobile clinics and community health workers are slowly making a difference. We must not underestimate the power of education paired with accessibility.

You people act like this is some kind of miracle. I’ve seen women cry after getting the HPV shot because they were told it would save them from cancer.

What about the ones who still get it anyway? What about the ones who die because their insurance denied the colposcopy?

You’re selling hope. I sell truth.

This is one of those rare posts that actually makes me feel hopeful. Not because the problem is solved, but because the tools are here and the science is solid.

It’s not about being perfect. It’s about showing up. Even if it’s just one person getting screened, that’s a win.

The data shows a 90% reduction in precancerous lesions in vaccinated cohorts. That’s not anecdotal. That’s statistically significant. The meta-analyses from Cochrane and Lancet Oncology are unequivocal.

Dismissing this as corporate propaganda ignores the entire epidemiological framework of oncology in the 21st century.

There is a quiet dignity in prevention. We do not need to suffer to prove our worth. The vaccine is not a surrender to biology-it is a collaboration with it.

Screening is not fear. It is care. And self-collection? That is liberation. Imagine a woman in a village, alone, holding the swab, choosing to protect herself. That is power.

so like... if i got the vaccine at 12 and now i’m 30 and i’ve never had a pap... am i just gonna be fine? like... i mean... it’s not like i’m having sex with 10 people a week so... idk

The assertion that HPV vaccination negates the necessity of screening is medically unsound and potentially lethal. The FDA, CDC, and WHO have uniformly reaffirmed that vaccinated individuals remain subject to the same screening protocols as unvaccinated individuals. To suggest otherwise constitutes a gross misrepresentation of clinical guidelines and endangers public health.