When a generic drug hits the shelf, how do we know it works just like the brand-name version? It’s not about matching the pill’s color or shape. It’s about matching what happens inside your body. That’s where Cmax and AUC come in - two simple numbers that tell regulators whether a generic drug will do the same job as the original.

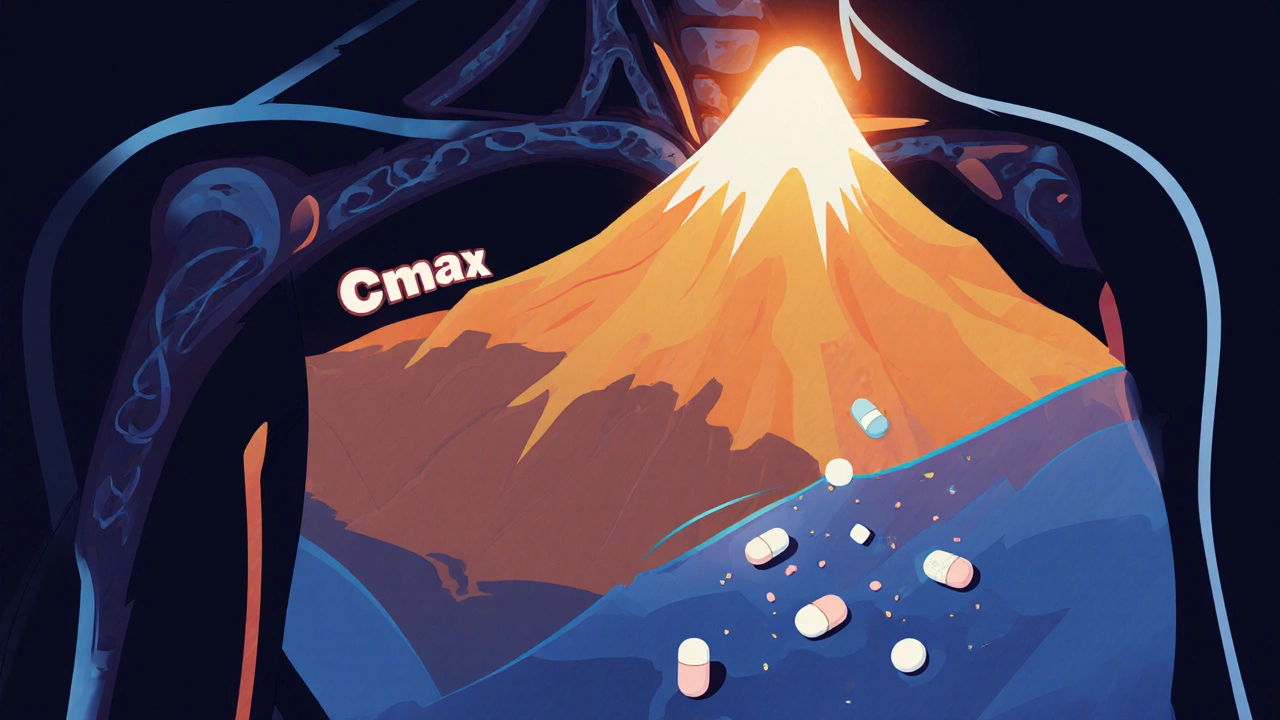

Cmax stands for maximum concentration. It’s the highest level a drug reaches in your blood after you take it. Think of it like the peak of a mountain on a graph. If you take a painkiller and it hits 8.1 mg/L in your bloodstream, that’s your Cmax. This number tells you how fast the drug gets into your system - its absorption rate.

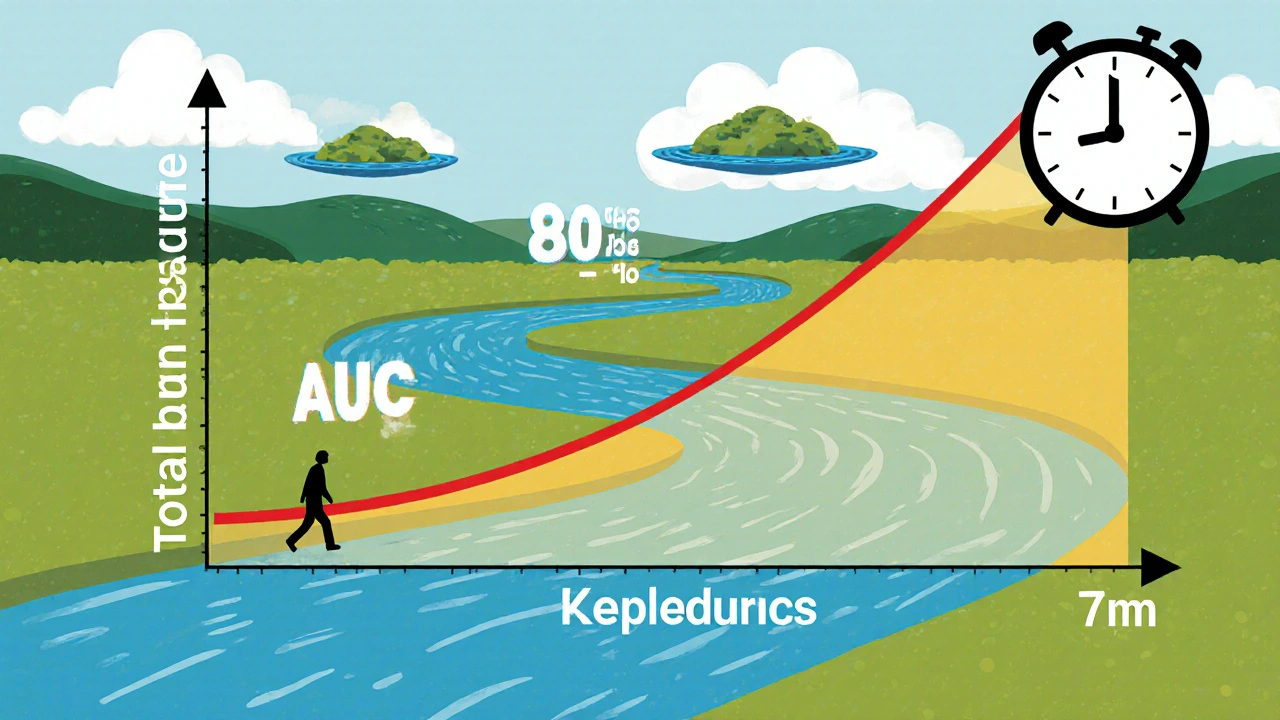

AUC, or area under the curve, measures total exposure. It’s the entire space under the blood concentration graph from the moment you swallow the pill until the drug is mostly gone. Measured in mg·h/L, AUC shows how much of the drug your body has been exposed to over time. If your AUC is 124.9 mg·h/L, your body absorbed and held onto that drug for a certain duration.

Here’s why both matter: A drug like ibuprofen needs a quick Cmax to relieve pain fast. But a drug like warfarin - used to prevent blood clots - needs consistent AUC. Too little exposure, and it doesn’t work. Too much, and you risk dangerous bleeding. So Cmax tells you about speed, AUC tells you about total dose delivered.

Regulators don’t just check one. They demand both Cmax and AUC pass the same test. Why? Because a drug could have the same total exposure (AUC) but hit too high too fast (Cmax), causing side effects. Or it could be absorbed slowly (low Cmax) but still deliver the same total dose (same AUC), making it ineffective for conditions needing quick action.

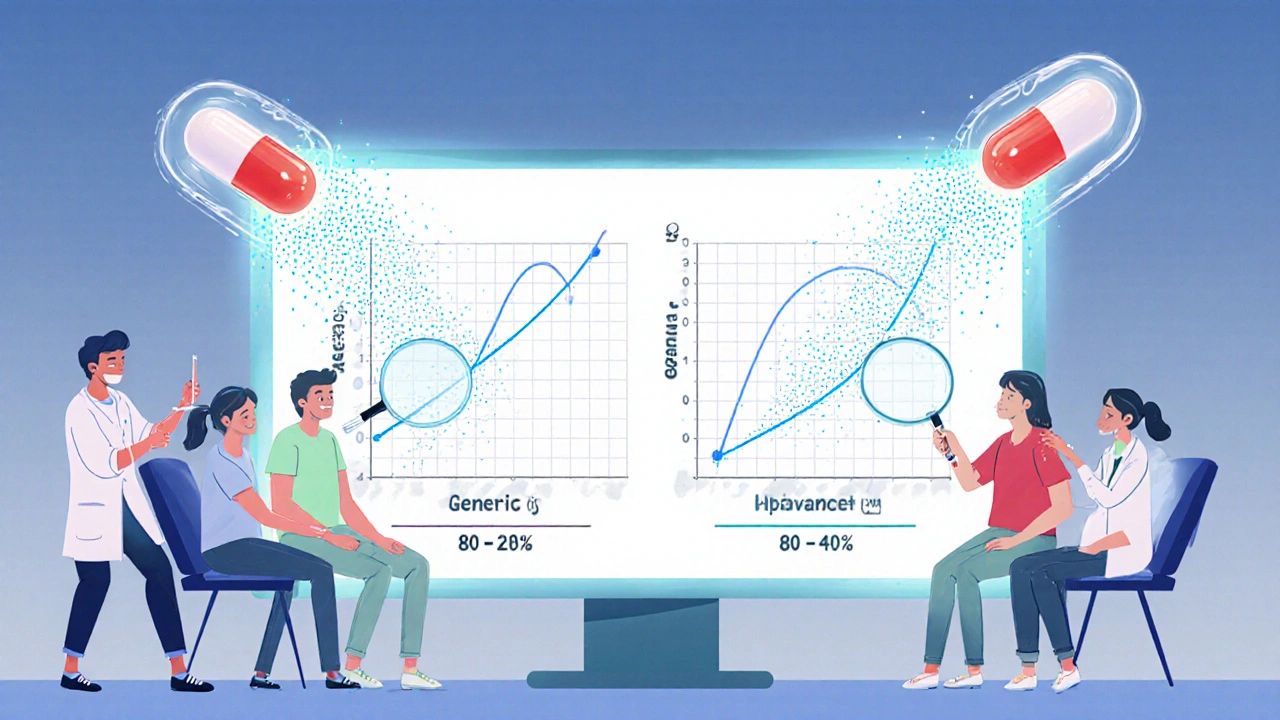

Take a study from 2007 comparing an innovator drug and its generic. The innovator had a Cmax of 8.1 mg/L. The generic was 7.6 mg/L - close, but not identical. AUC was 124.9 vs. 112.4 mg·h/L. The ratios were 94% for Cmax and 90% for AUC. Both fell within the acceptable range. So even though numbers weren’t identical, the difference wasn’t clinically meaningful.

The rule? Both Cmax and AUC must fall between 80% and 125% of the brand-name drug’s values. This isn’t arbitrary. It comes from decades of data showing that differences outside this range can affect how well a drug works or how safe it is. The 80-125% window is based on logarithmic statistics because drug concentrations in blood don’t follow a normal bell curve - they follow a log-normal one. This means the math has to be done on the log scale to be accurate.

You might wonder: why 80-125%? Why not 90-110%? The answer lies in statistical safety. In the early 1990s, experts at the BioInternational conference analyzed real-world data and found that a 20% difference in exposure - whether higher or lower - rarely led to noticeable clinical changes in most patients. That’s why the 80-125% range became the global standard.

It’s symmetrical on a log scale: ln(0.8) = -0.2231 and ln(1.25) = 0.2231. This symmetry makes the math work cleanly in crossover studies, where each participant takes both the brand and generic versions at different times. It also accounts for natural variation between people - some absorb drugs faster, others slower. The 80-125% range allows for that biological noise without risking safety.

But there are exceptions. For drugs with a narrow therapeutic index - like lithium, digoxin, or levothyroxine - even a 10% change can cause problems. That’s why the EMA recommends tighter limits of 90-111% for these drugs. The FDA also allows scaled bioequivalence for highly variable drugs, where the range widens based on how much the drug varies between individuals. But for most pills you take daily, the 80-125% rule still applies.

Testing isn’t done on sick patients. It’s done on healthy volunteers - usually 24 to 36 people. Each person gets both the brand and generic versions in a random order, with a washout period in between. Blood is drawn 12 to 18 times over 3 to 5 half-lives of the drug. For a fast-acting drug like aspirin, samples might be taken every 15-30 minutes in the first two hours to catch the Cmax peak.

Why so many samples? Because missing a single time point can ruin the Cmax estimate. Industry data shows that about 15% of failed bioequivalence studies are due to poor sampling during absorption. If you don’t sample often enough right after dosing, you might miss the true peak. That’s why guidelines insist on using actual sampling times, not just scheduled ones.

Once the data is collected, it’s analyzed using specialized software like Phoenix WinNonlin. The values are log-transformed, ratios are calculated, and 90% confidence intervals are built. If both AUC and Cmax intervals fall within 80-125%, the drugs are declared bioequivalent.

Over 1,200 generic drugs were approved by the FDA in 2022 alone. Almost all of them passed the Cmax and AUC tests. A 2019 analysis of 42 studies in JAMA Internal Medicine found no meaningful difference in effectiveness or safety between generics and brand-name drugs - as long as they met bioequivalence standards.

That’s why pharmacists can swap generics for brands without asking your doctor. It’s not a gamble. It’s science. The global bioequivalence testing market is worth over $2 billion and growing. Countries from Brazil to India to South Africa now use the same 80-125% standard, thanks to harmonization efforts led by the WHO and ICH.

But it’s not perfect. Some drugs - especially modified-release pills or those with complex absorption patterns - don’t fit neatly into the Cmax/AUC model. That’s why the FDA is exploring partial AUC analysis for extended-release formulations. And for drugs like levothyroxine, where tiny changes can throw off thyroid levels, regulators are pushing for stricter limits.

If you’re taking a generic drug, you’re not getting a second-rate version. You’re getting a product that has been tested with the same rigor as the brand. The numbers Cmax and AUC are the invisible gatekeepers. They ensure that whether you buy the brand or the copy, your body gets the same dose, at the same speed, over the same time.

There’s no need to worry about switching. If your generic looks different, tastes different, or costs less - that’s fine. The active ingredient is the same. The way your body handles it? Also the same. That’s the power of Cmax and AUC. They turn abstract science into real-world trust.

While Cmax and AUC remain the gold standard, new tools are emerging. Modeling and simulation are being tested to predict bioequivalence without running full human trials. But experts agree: for now, nothing beats real human data. As Dr. Robert Lionberger from the FDA said in 2022, “AUC and Cmax will remain the primary endpoints for conventional drugs for the foreseeable future.”

Why? Because they’ve been tested for over 30 years. Because they work. Because millions of people rely on them every day.

Cmax stands for maximum plasma concentration - the highest level a drug reaches in your bloodstream after taking it. It shows how quickly the drug is absorbed. In bioequivalence studies, the Cmax of a generic drug must be within 80-125% of the brand-name drug’s Cmax to prove similar absorption speed.

AUC, or area under the curve, measures total drug exposure over time. It’s calculated from the area under the blood concentration-time graph. AUC tells you how much of the drug your body has absorbed overall. For bioequivalence, the AUC of a generic must be between 80% and 125% of the brand-name drug’s AUC.

Because they measure different things. Cmax reflects the rate of absorption - how fast the drug enters your system. AUC reflects total exposure - how much drug your body receives over time. A drug could have the same AUC as the brand but a much higher Cmax, causing side effects. Or it could have a low Cmax and take too long to work. Both must meet the 80-125% range to ensure safety and effectiveness.

For most drugs, yes. The 80-125% range is used by the FDA, EMA, WHO, and over 120 countries. But for drugs with a narrow therapeutic index - like warfarin, levothyroxine, or digoxin - tighter limits (90-111%) may be applied. Some regulators also allow wider limits for highly variable drugs using scaled bioequivalence, but this requires extra justification.

Yes, for most conventional drugs. Studies are done in 24-36 healthy adults to avoid complications from disease or other medications. Blood samples are taken frequently over 3-5 drug half-lives to accurately capture Cmax and AUC. For some complex formulations (like extended-release), studies may involve patients, but that’s rare and requires special approval.

Yes. Two drugs can have the same active ingredient but different inactive ingredients, manufacturing processes, or tablet coatings. These can affect how fast the drug dissolves or is absorbed. That’s why Cmax and AUC are measured - to test real-world performance, not just chemical composition. Many generics fail their first bioequivalence test and need reformulation.

No. Standard Cmax and AUC rules apply to immediate-release oral tablets and capsules. For extended-release, inhaled, or injectable drugs, different methods may be used. The FDA and EMA have specific guidelines for these. For example, partial AUC (AUC from 0-4 hours) might be used for drugs with multiple absorption peaks. But for most pills you take daily, Cmax and AUC remain the standard.

14 Responses

lol so basically we're trusting math that's been around since the 90s to keep us from dying? cool. i'll just take my generic and hope the FDA didn't nap during the review. 🤷♂️

The bioequivalence thresholds-80% to 125%-are derived from logarithmic transformation of pharmacokinetic data, which inherently accounts for the log-normal distribution of plasma concentrations; this is not arbitrary, nor is it a compromise.

America’s generic drug system is the most advanced on Earth. Europe? Still stuck in the 2000s. China? Don’t even get me started. We didn’t build this empire by guessing-we built it with math. 🇺🇸🔥

Honestly, this is one of those topics where people panic over nothing. If your blood levels are within 80-125%, you’re getting the same medicine. The pill might look different, but your body doesn’t care about the logo. 💊✨

I switched to generics years ago. Saved $300/month. No side effects. No drama. Just science.

This is brilliant. I mean, really. Who knew that a few numbers could keep millions of people alive? We take this for granted. Respect. 🙏

The 80-125% range is not a loophole-it’s a statistically validated safety margin based on decades of clinical data. It accounts for inter-individual variability, assay error, and biological noise. To dismiss it as 'arbitrary' is to misunderstand pharmacokinetics entirely.

Let’s be real: if the generic didn’t pass, it wouldn’t be on the shelf. The fact that you’re even questioning this means you’ve never read the FDA guidance. Or maybe you just like fear-mongering. Either way, stop.

Funny how we trust a pill more than we trust each other. We’ll scrutinize a $5 generic like it’s a nuclear launch code, but hand over our data to a tech company for free. The real question isn’t about Cmax-it’s about why we fear the simple, and worship the complex.

I just got my thyroid meds switched to generic last month. I’ve been crying every night. I know it’s irrational, but I feel betrayed. Like my body doesn’t trust me anymore. 😭

Look, I get why people are nervous. I used to be one of them. But here’s the thing: bioequivalence isn’t about perfection-it’s about predictability. The 80-125% range? It’s not a guess. It’s a bell curve built on thousands of real human responses. If your generic passed, your body is getting what it needs. No magic, no conspiracy-just good science. And if you’re still worried? Talk to your pharmacist. They’ve seen this a thousand times. They’ll tell you the same thing I’m saying: you’re fine.

I must insist that the European Medicines Agency’s 90–111% threshold for narrow-therapeutic-index drugs is not merely prudent-it is a moral imperative. The American 80–125% standard, while statistically defensible, remains dangerously permissive in the context of levothyroxine, digoxin, and warfarin. This is not a technical disagreement-it is a failure of regulatory foresight. The U.S. FDA must align with EMA standards to prevent iatrogenic harm. I have reviewed the literature. I am not exaggerating.

So let me get this straight: we let Big Pharma sell us a $500 brand-name drug, then let some lab in India slap a different label on the exact same powder and sell it for $5? And we call that ‘science’? Nah. That’s capitalism with a lab coat. Cmax? AUC? Just fancy words to make us feel better about getting ripped off. The real bioequivalence? Your wallet’s empty and your trust is gone.

The sampling frequency during bioequivalence studies is critical: missing even one peak time point can skew Cmax by as much as 15–20%. That’s why guidelines mandate actual sampling times-not scheduled-and why studies require 12–18 blood draws over 3–5 half-lives. This isn’t bureaucracy; it’s precision medicine in action. The data must be exact, because human lives depend on it.