When someone overdoses on medication, the emergency team rushes in. They give naloxone. They pump the stomach. They stabilize breathing. And then, often, they send the person home with a warning: don’t do it again.

But what happens after they leave the hospital? That’s where the real damage begins.

Most people think of overdose as a one-time crisis. But for survivors, it’s often the start of a lifelong health battle. Even if you survive, your body doesn’t just bounce back. The long-term effects of medication overdose can reshape your brain, your organs, and your mental health - sometimes permanently.

The brain needs oxygen to function. Just four minutes without it, and brain cells start dying. In an overdose, especially with opioids or benzodiazepines, breathing slows or stops. Oxygen levels crash. The brain starves.

Studies show that 63% of overdose survivors have lasting memory problems. Short-term memory? Gone. Long-term memory? Patchy. You forget names, appointments, even how to do simple tasks you used to do without thinking.

It’s not just memory. Nearly 57% struggle with concentration. 38% lose fine motor control - buttoning a shirt, holding a cup, typing becomes hard. 35% have trouble speaking clearly. Some can’t find the right words. Others repeat themselves without realizing it.

And then there’s brain fog. Not the kind you get from lack of sleep. This is thick, heavy, constant. One survivor on Reddit wrote: "It’s been two years. I still can’t remember what I had for breakfast. My husband tells me I ask the same question five times an hour. I don’t even know I’m asking it."

Why does this happen? Toxic chemicals from the overdose disrupt neurotransmitters - the brain’s messaging system. The National Institute on Drug Abuse found that 78% of survivors have permanent changes in dopamine, serotonin, and GABA systems. These aren’t just chemical imbalances. They’re structural. Brain tissue is damaged.

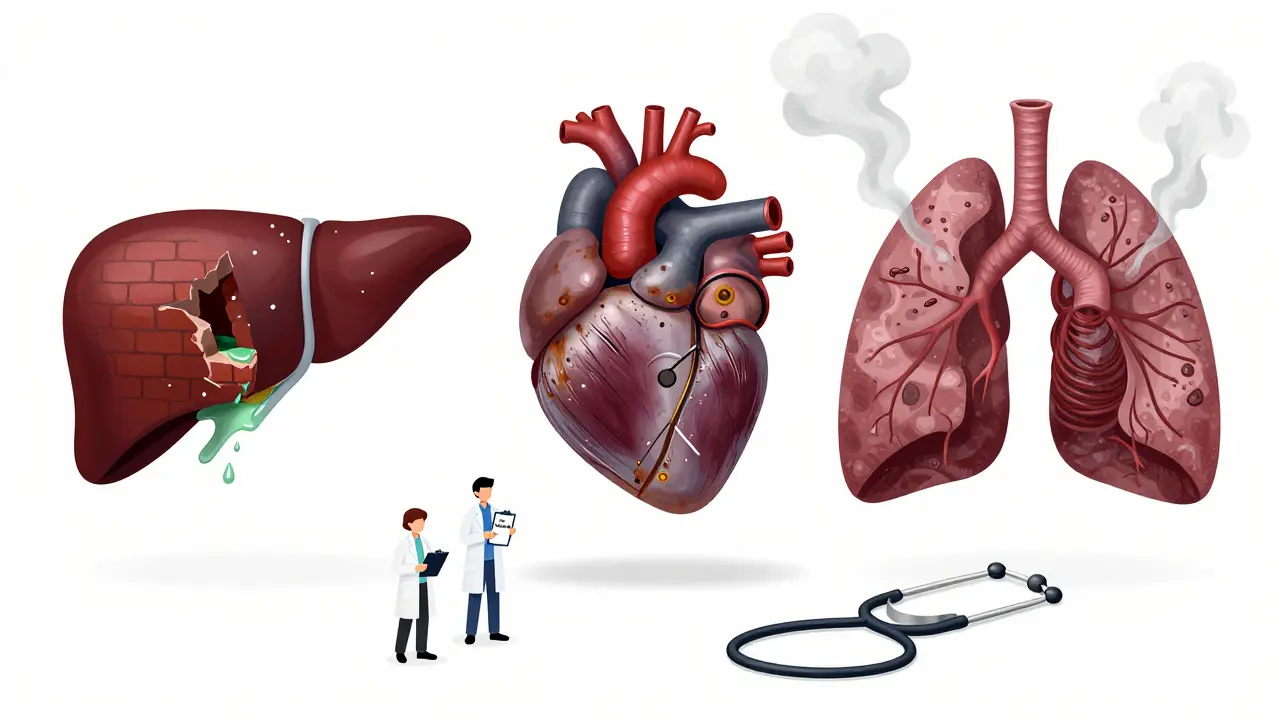

The brain isn’t the only organ that pays the price.

Opioid overdoses cause respiratory depression. Lungs stop working. Oxygen drops. Kidneys get damaged. 22% of non-fatal opioid overdose survivors develop chronic kidney problems. The heart struggles too - 18% face long-term heart rhythm issues or high blood pressure. And because vomiting is common during overdose, many inhale stomach contents. That leads to pneumonia. 6% of survivors deal with recurring lung infections years later.

Benzodiazepine overdoses - like taking too many Xanax or Valium - don’t just slow breathing. They leave the nervous system in chaos. 27% of survivors still have trouble making decisions, planning, or staying focused six months after the overdose. It’s not depression. It’s not laziness. It’s neurological damage.

Stimulant overdoses - from Adderall, Ritalin, or even too many diet pills - hit the heart hard. 31% of survivors develop chronic high blood pressure or irregular heartbeats. Their arteries stiffen. Their heart muscle weakens. Many end up on lifelong medication just to keep their heart from failing.

And then there’s paracetamol (acetaminophen). It’s in so many painkillers. People think it’s safe. But take too much, and your liver starts dying. Symptoms don’t show up for 48 to 72 hours. By then, it’s often too late. 45% of those who don’t get treatment within 8 hours develop cirrhosis or liver failure. No warning. No pain. Just silent destruction.

Surviving an overdose doesn’t mean you’re fine. It means you’re now carrying a trauma.

73% of survivors develop a diagnosable mental health condition. PTSD? 41%. Major depression? 38%. Generalized anxiety? 33%. These aren’t temporary reactions. They’re persistent. The SAMHSA survey found that 58% still had these conditions after 12 months.

Dr. Sarah Wakeman from Massachusetts General Hospital says: "The near-death experience rewires the brain. You’re not just recovering from a drug - you’re recovering from the terror of dying."

Many survivors feel guilt. Shame. Fear. They don’t want to talk about it. They avoid doctors. They stop taking medications they need because they’re afraid of another overdose. Some isolate themselves. Others turn back to drugs as a way to numb the emotional pain.

And here’s the cruel twist: only 28% of overdose survivors get proper mental health care within 30 days of leaving the hospital. The system treats the overdose like a mistake - not a medical emergency with lifelong consequences.

Most hospitals don’t have protocols for long-term care after overdose. The HHS ASPE report found that 41% of patients were discharged without any referral for follow-up - not for brain scans, not for therapy, not for liver checks.

Emergency rooms focus on survival. They don’t plan for recovery. They don’t test for cognitive decline. They don’t schedule neurology appointments. They don’t check liver enzymes three months later.

Even when they do, it’s patchy. Only 47% of emergency departments document the expected long-term monitoring for overdose survivors. That means doctors don’t know what to look for. Nurses don’t know what to ask. Families don’t know what to watch for.

And in rural areas? The delays are deadly. The average time to give naloxone in rural towns is over 22 minutes. By then, brain damage is already done. But no one tracks it. No one reports it.

The financial toll is staggering. The average lifetime cost of care for a survivor with permanent brain damage? Over $1.2 million. That’s therapy, medications, home care, lost wages, specialized equipment.

Compare that to someone who survives without lasting damage: under $300,000. The difference isn’t luck. It’s time. Minutes matter.

And yet, only 19% of U.S. hospitals have formal programs to monitor long-term effects. Only 31% of counties offer specialized neurological rehab for overdose survivors. Most people are left to figure it out alone.

The Biden Administration’s 2023 funding for brain injury research is a start. But experts say it’s still underfunded by 87%. The National Institute on Aging is now tracking 2,500 survivors over 10 years. Early data shows overdose survivors age cognitively 7.3 years faster than their peers. One overdose = seven extra years of brain decline.

If you or someone you know survived an overdose, don’t assume it’s over. The recovery has just begun.

The system isn’t designed for survivors. But you can be your own advocate. Your life after an overdose doesn’t have to be defined by damage. But you have to demand care - because no one else will.

Full recovery is rare. While some physical symptoms like nausea or fatigue may fade, the neurological, organ, and psychological damage often lasts. Studies show that 68% of non-fatal overdose survivors develop at least one chronic health condition directly tied to the overdose. Memory, balance, decision-making, and emotional regulation can be permanently altered. Early and ongoing medical care improves outcomes, but complete reversal of damage is uncommon.

Some effects show up immediately - confusion, weakness, memory lapses. Others take months or years. Liver damage from paracetamol can take 48-72 hours to become visible. Cognitive decline, mood disorders, and organ deterioration often emerge over 6-18 months. This delay is why follow-up care is critical. Symptoms that seem unrelated - like trouble concentrating at work or falling more often - may be linked to the overdose.

Opioids (like fentanyl, oxycodone) cause brain hypoxia and heart damage. Benzodiazepines (like Xanax, Valium) lead to lasting cognitive impairment and memory loss. Stimulants (like Adderall, Ritalin) damage the heart and nervous system. Paracetamol (acetaminophen) causes delayed, severe liver failure. Even "safe" medications become dangerous in high doses, and all can leave lasting harm if not treated quickly.

Some brain functions can improve with therapy, time, and support - especially if treatment starts within hours. But permanent structural damage to brain cells does not reverse. Neuroplasticity can help the brain reroute signals, but lost neurons are gone. Memory, speech, and motor control may improve with rehab, but they rarely return to pre-overdose levels. The goal isn’t full recovery - it’s maximizing function and quality of life.

Most emergency departments are designed to treat acute crises - not chronic conditions. Overdose is often seen as a behavioral issue rather than a medical one. Only 19% of U.S. hospitals have formal protocols for long-term monitoring. Without funding, guidelines, or standardized procedures, survivors are discharged without referrals, tests, or follow-up plans - leaving them vulnerable to worsening health.

Yes. Family members can insist on neurological and organ function tests after discharge. They can track symptoms like memory loss, confusion, mood changes, or balance problems. They can push for referrals to neurologists, therapists, or addiction specialists. They can also learn how to recognize early signs of another overdose - and carry naloxone. Their advocacy can be the difference between lifelong disability and meaningful recovery.

13 Responses

lol so the system is designed to let you die quietly after you survive? 🤡

we give you naloxone then ghost you like a bad date. next time, just skip the hospital and go straight to the afterlife. less paperwork.

this hits hard man i never thought about how the brain just stops working for a few minutes and then you’re never the same

it’s not a mistake it’s a trauma and we treat it like a bad choice

The data presented here is both compelling and alarming. It underscores a systemic failure in post-overdose care that warrants immediate policy intervention. The neurological, cardiac, and hepatic sequelae are not incidental-they are predictable and preventable with structured follow-up protocols.

You know what’s worse than the overdose? The fact that people think this is just about drugs. It’s about weakness. If you had more discipline, you wouldn’t be here. And now we’re supposed to spend $1.2 million on someone who chose to destroy themselves?

this is wild i had no idea paracetamol could do this

my uncle took 20 pills for a headache and now he cant remember my name

he just smiles and says hi like its new

73% develop mental health issues? Shocking. But let’s be real - most of them were already broken. This isn’t damage from the overdose. It’s the overdose exposing the rot underneath. Stop romanticizing addiction as a tragedy. It’s a character flaw.

There is a profound ethical failure here. The moment we reduce human suffering to a cost-benefit analysis, we abandon medicine itself.

Survival is not the endpoint. Recovery - full, dignified, sustained recovery - must be the goal. The fact that we don’t measure brain function post-overdose is not negligence. It is moral abandonment.

I work in a hospital. I see this every week. We discharge people with a pamphlet and a prayer. No follow-up. No scans. No therapy referrals. It’s not that we don’t care - it’s that the system is broken. We’re all just running on fumes.

But we can change it. Start by asking for a neuro consult. Always.

I’ve been there. Took too much oxycodone after surgery. Woke up two days later with my wife crying and a neurologist asking me to spell ‘world’ backwards. I couldn’t. I still can’t remember what I had for lunch yesterday. But I’m alive. And I’m learning. You don’t have to be fixed to be worthy.

hey if you or someone you know went through this - you’re not alone. seriously. i lost my brother to this and now i help people get follow-up care. it’s messy. it’s hard. but it’s worth it. reach out. ask for help. you don’t have to do this alone.

You think this is bad? Wait till you see the 60-year-old who OD’d on Xanax in '98 and now walks around like a confused ghost, muttering about his dead dog and forgetting how to use a fork. The system doesn’t care. The doctors don’t care. The family pretends it never happened. That’s the real horror story - the silence.

why are we even talking about this like its a medical issue? just dont do drugs. problem solved. save the money. let nature take its course.

I’m so proud of the people who shared their stories here. You’re not broken. You’re surviving. And that’s more than most people ever do. Keep pushing. Keep asking. Keep showing up. We see you. We’re with you.