When your skin breaks out in thick, red, scaly patches, it’s easy to think it’s just a cosmetic issue. But if those patches come with stiff, swollen fingers, aching heels, or lower back pain, you’re not just dealing with a skin problem-you’re dealing with an autoimmune disease that’s attacking your body from the inside out. Psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis (PsA) are two sides of the same coin: one visible on the skin, the other hidden in the joints. And while they often show up together, many people don’t realize they’re connected until the damage is already done.

Psoriatic arthritis isn’t just arthritis that happens to occur in someone with psoriasis. It’s a full-blown autoimmune condition where the immune system turns against healthy tissues-both in the skin and the joints. About 30% of people with psoriasis will develop PsA, according to the American College of Rheumatology. In most cases, the skin condition comes first, often years before the joint pain starts. But in 5 to 10% of cases, joint swelling and pain appear before any skin symptoms show up, making diagnosis trickier.

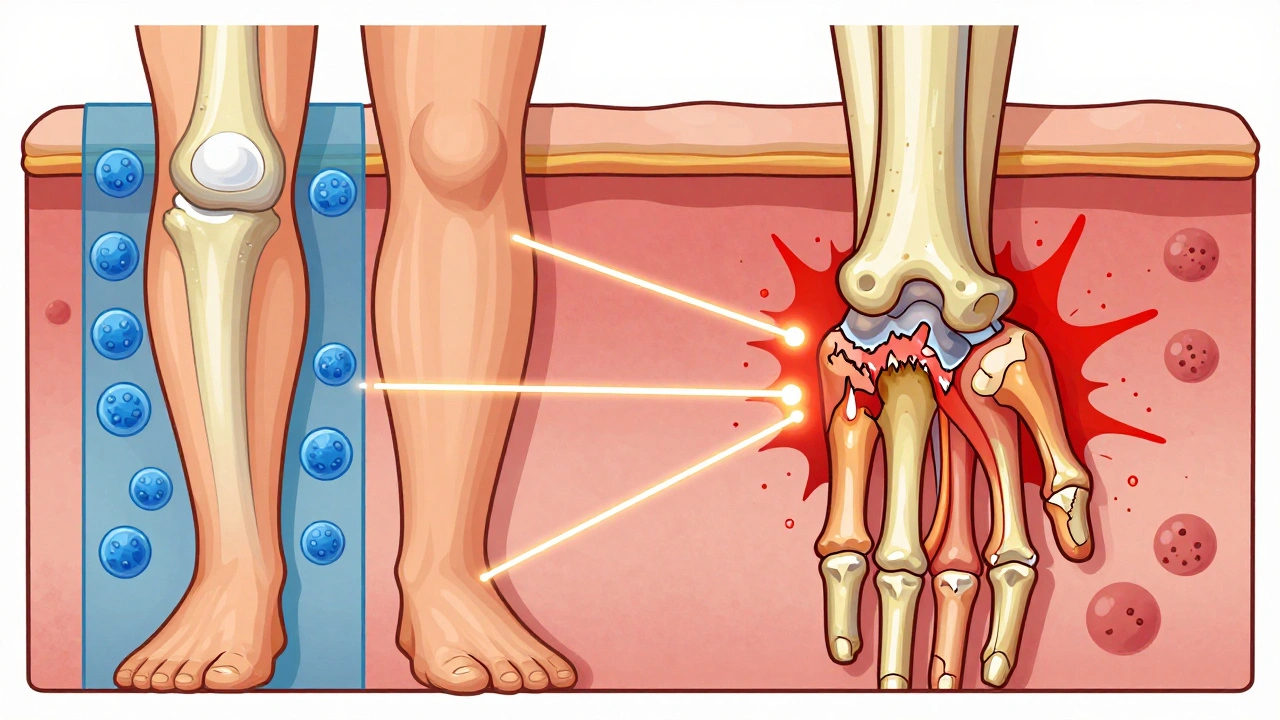

The hallmark of PsA isn’t just joint pain. It’s the way it hits different parts of the body in unique ways. You might notice one or two fingers swelling up like sausages-that’s dactylitis, and it affects nearly 4 in 10 people with PsA. Or you might feel sharp pain at the bottom of your foot or behind your ankle, where tendons attach to bone. That’s enthesitis, present in up to half of all PsA patients. These aren’t random symptoms. They’re clues that your immune system is firing off in multiple directions at once.

Psoriasis shows up as raised, red plaques covered with silvery scales, usually on elbows, knees, scalp, or lower back. But behind those flakes is a storm of inflammation. Immune cells rush to the skin, triggering rapid skin cell growth. The same immune signals-especially those involving tumor necrosis factor (TNF-alpha) and interleukin-17-also target joints, tendons, and even the spine.

Genetics play a big role. People with certain HLA genes-like HLA-B27, HLA-B38, or HLA-B39-are more likely to develop PsA. But genes alone don’t cause it. Environmental triggers like stress, infections, injury, or even smoking can flip the switch. And once it starts, the inflammation doesn’t stop on its own. Left untreated, it can permanently damage cartilage and bone.

There’s no single test that confirms psoriatic arthritis. Doctors rely on the CASPAR criteria, a set of rules developed in 2006 to make diagnosis more accurate. To meet the criteria, you need inflammatory joint disease plus at least three of these:

A score of 3 or higher means PsA is likely. But tests still matter. Blood work checks for inflammation markers like CRP and ESR. X-rays or MRIs can show early bone erosion or the telltale “pencil-in-cup” deformity-where bone is both worn down and rebuilt in strange shapes. Ultrasound can spot inflammation in tendons before it shows up on an X-ray. And sometimes, a skin biopsy is done just to rule out eczema or fungal infections that look similar.

PsA doesn’t just hurt. It steals your life. Joint damage can happen fast-in as little as two years if untreated. By the time many people get diagnosed, they already have irreversible bone changes. But the damage isn’t just in the joints. PsA is a systemic disease, meaning it affects your whole body.

Up to half of people with PsA have metabolic syndrome-high blood pressure, belly fat, insulin resistance, and bad cholesterol. That means a 43% higher risk of heart attack. Depression and anxiety are twice as common in PsA patients as in the general population. Quality of life scores are 30 to 40% lower. And mortality? It’s 30 to 50% higher, mostly because of heart disease.

This isn’t just about managing pain. It’s about survival. Treating the inflammation isn’t optional-it’s life-saving.

Not all treatments are created equal. For mild joint pain, NSAIDs like ibuprofen can help. But they don’t stop the disease. If symptoms stick around, doctors move to DMARDs like methotrexate, which slow down immune activity. But for moderate to severe PsA, the real game-changers are biologics-drugs that target specific parts of the immune system.

Here’s what works:

Doctors now pick treatments based on what’s most active in your body. If your back hurts and your heels are stiff, go with a TNF blocker. If your skin is still flaring despite joint treatment, switch to an IL-17 drug. The goal isn’t just less pain-it’s minimal disease activity: no swollen joints, less than 1% skin involvement, no fatigue, and daily function near normal.

Research is moving fast. Scientists now believe the gut microbiome plays a role. People with PsA have different gut bacteria than those without it. Could changing your gut flora help? Clinical trials are testing probiotics and dietary changes alongside medication.

New biomarkers are emerging too. Blood tests for calprotectin and MMP-3 might soon predict who will develop severe PsA before symptoms even start. And drugs like deucravacitinib (a TYK2 inhibitor) and bimekizumab (which blocks both IL-17A and IL-17F) are showing even better results in trials.

By 2027, experts predict 70% of PsA patients will be on advanced therapies within two years of diagnosis. That’s up from just 40% today. Why? Because early treatment prevents damage. The longer you wait, the harder it is to reverse what’s been done.

Medication helps-but it’s not the whole story. Exercise keeps joints flexible and reduces inflammation. Low-impact activities like swimming, cycling, or yoga are ideal. Weight loss matters too. Losing even 5% of body weight can cut inflammation markers and improve drug response.

Stress management isn’t fluffy advice. Chronic stress worsens flare-ups. Mindfulness, therapy, or even just setting boundaries to protect your energy can make a real difference.

And don’t ignore your mental health. Depression and PsA feed off each other. If you’re feeling hopeless, tired all the time, or losing interest in things you used to love-say something. Treatment for depression works. And it helps your joints too.

If you have psoriasis and notice new joint stiffness, especially in the morning, or if your nails are pitting or lifting, don’t wait. See a rheumatologist. Don’t settle for “it’s just aging” or “it’s probably gout.” PsA is treatable-but only if caught early.

The future of PsA care is personalized. Blood tests, imaging, and symptom tracking will guide treatment choices. But right now, the most powerful tool you have is awareness. Know the signs. Speak up. And remember: this isn’t just skin deep. It’s systemic. It’s serious. And it’s manageable.

Not exactly. Psoriasis doesn’t “turn into” psoriatic arthritis. They’re two separate manifestations of the same underlying autoimmune condition. About 30% of people with psoriasis will develop joint symptoms, but not everyone does. The immune system’s response is what links them-not the skin condition itself turning into arthritis.

No. Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) usually affects small joints symmetrically-both hands, both wrists-and tests positive for rheumatoid factor or anti-CCP antibodies. Psoriatic arthritis often affects joints unevenly, causes dactylitis (sausage fingers), enthesitis (tendon pain), and is linked to psoriasis or nail changes. RA is negative for these signs. Blood tests help tell them apart.

Yes, but it’s rare. About 5 to 10% of people with PsA don’t have visible skin psoriasis at diagnosis. But most of them have a family history of psoriasis, or will develop it later. Nail changes, like pitting or lifting, are often the only clue. Doctors rely on the CASPAR criteria to diagnose these cases.

Diet doesn’t cure PsA, but it can influence inflammation. Losing weight reduces joint stress and lowers inflammatory markers. Some people report improvement with anti-inflammatory diets-rich in fish, vegetables, nuts, and olive oil-and by avoiding processed foods, sugar, and alcohol. There’s no one-size-fits-all diet, but if you’re overweight, even a 5% weight loss can make a measurable difference in symptoms.

Biologics are generally safe for long-term use when monitored. They do increase the risk of infections like tuberculosis or fungal infections, so screening is required before starting. Regular blood tests and check-ups help catch issues early. The benefits-preventing joint damage, reducing heart risk, improving quality of life-far outweigh the risks for most people with moderate to severe PsA.

There’s no cure yet. But with early, aggressive treatment, many people achieve long-term remission or minimal disease activity. That means no pain, no swelling, no skin flares, and normal daily function. Some people stay in remission for years, even after stopping medication. The goal isn’t just control-it’s living well.

If you’re on treatment, check-ins every 3 to 6 months are typical. Your doctor will assess joint counts, skin involvement, blood markers, and how you’re feeling. Imaging like X-rays or MRIs may be repeated yearly or every two years to track damage. If you’re in remission, visits may space out, but ongoing monitoring is still essential to catch flare-ups early.

7 Responses

When I first got diagnosed with psoriasis, I thought it was just a weird skin thing I had to deal with. Then my fingers started swelling up like sausages and I couldn’t grip my coffee mug. Turns out, it wasn’t just my skin-it was my whole body screaming for help. I wish someone had told me earlier that this wasn’t normal aging or overwork. If you’ve got psoriasis and any joint pain, don’t wait. See a rheumatologist. Your future self will thank you.

Just to clarify: psoriatic arthritis isn't an extension of psoriasis-it's a parallel autoimmune response. The same inflammatory pathways (TNF-alpha, IL-17) drive both skin plaques and joint destruction. That's why biologics targeting those cytokines work for both. Many patients don't realize that treating the skin alone won't stop joint damage. You need systemic control. Also-yes, nail pitting is a huge red flag. Don't ignore it.

I had psoriasis for 12 years before I got diagnosed with PsA. I thought my back pain was from sitting too much at my desk. Turns out, it was enthesitis. My doctor didn't even ask about my skin when I mentioned the back pain. That's the problem. Most GPs don't connect the dots. If you have psoriasis and any unexplained joint or tendon pain, push for a referral. Don't let them dismiss it as 'just arthritis.' It's not.

Let's be real-most people with psoriasis are lazy about their health. They think 'it's just skin' and ignore the joint pain until it's too late. Then they wonder why they can't walk. Biologics aren't magic, but they're not scary either. You get screened for TB, you get blood work, you take the meds. It's not a death sentence. It's a lifeline. Stop waiting for it to get worse. Start treating it before your joints turn to dust.

I’ve been on ustekinumab for three years now. My skin is 95% clear, and my joints don’t ache anymore. But I didn’t just take the pill and call it a day-I changed my diet, started swimming three times a week, and got therapy for the anxiety that came with the diagnosis. Medication helps, but lifestyle isn’t optional. It’s part of the treatment plan. And if you’re struggling emotionally, please talk to someone. This disease eats at your mind as much as your body.

Anyone who says 'diet fixes PsA' is selling something. Yes, weight loss helps-but it doesn't reverse autoimmune damage. Biologics do. And if you're not on one after two years of symptoms, your doctor is either outdated or incompetent. The data is clear: early aggressive treatment prevents disability. Waiting for 'natural remedies' is like waiting for your house to burn down before calling the fire department.

Did you know that the gut microbiome is being manipulated by Big Pharma to make you dependent on biologics? They’ve known for years that dysbiosis triggers autoimmunity, but they don’t want you to fix it with probiotics or fasting-they want you on lifelong injections. I read a study in a journal no one talks about-Journal of Autoimmune Ecology-that showed 70% of PsA patients had severe candida overgrowth. The real cure? A 21-day antifungal cleanse, intermittent fasting, and avoiding gluten, dairy, and lectins. Biologics? They suppress symptoms while the root cause festers. The system doesn’t want you cured-it wants you managed. Wake up.